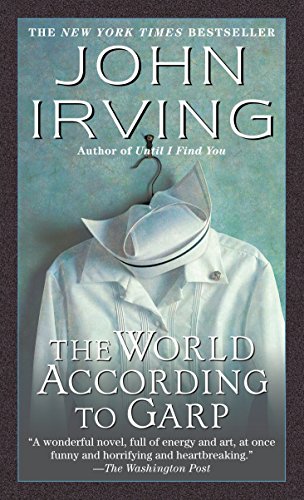

The World According to Garp

Winner of the National Book Award

“Nothing in contemporary fiction matches it.” —The New Republic

“Wonderful . . . full of energy and art, at once funny and horrifying and heartbreaking.” —Washington Post

Powerful and political, with unforgettable characters and timeless themes, The World According to Garp is John Irving’s breakout novel. The precursor of Irving’s later protest novels, it is the story of Jenny, an unmarried nurse who becomes a single mom and a feminist leader, beloved but polarizing—and of her son, Garp, less beloved but no less polarizing.

From the tragicomic tone of its first sentence to its mordantly funny last line—“we are all terminal cases”—The World According to Garp maintains a breakneck pace. The subject of sexual hatred and violence—of intolerance of sexual minorities, and sexual differences—runs through the book, as relevant now as ever. Available in more than forty countries—with more than ten million copies in print—Garp is a comedy with forebodings of doom.

“Nothing in contemporary fiction matches it.” —The New Republic

“Wonderful . . . full of energy and art, at once funny and horrifying and heartbreaking.” —Washington Post

Powerful and political, with unforgettable characters and timeless themes, The World According to Garp is John Irving’s breakout novel. The precursor of Irving’s later protest novels, it is the story of Jenny, an unmarried nurse who becomes a single mom and a feminist leader, beloved but polarizing—and of her son, Garp, less beloved but no less polarizing.

From the tragicomic tone of its first sentence to its mordantly funny last line—“we are all terminal cases”—The World According to Garp maintains a breakneck pace. The subject of sexual hatred and violence—of intolerance of sexual minorities, and sexual differences—runs through the book, as relevant now as ever. Available in more than forty countries—with more than ten million copies in print—Garp is a comedy with forebodings of doom.

BUY THE BOOK

Community Reviews

Not my first Irving book but the one of the two that I’ve enjoyed and not DNFed. I think the reason this one works for me is that it has more weight. This book has a lot of things to say that the other Irving I read seemingly did not, and it says all of that in a head-spinning narrative slammed full of humor and darkness.

This book is about a lot of things. You could pick out any of the main themes and arguing the book is wholly about them wouldn’t be difficult. If you are a new parent dealing with the anxieties of living in a dangerous world, you’ll find companionship and understanding here. If you’re grieving the loss of a parent or child you’ll get the same- one of the most central themes is of death. If you’re interested in this purely as a piece of feminist lit, you can certainly read and analyze it that way and there’s much to be said about it from that perspective. But to me, as a reader and a writer (and a man who always reads authors notes and introductions, and so usually can somewhat guess the author’s intent), this is primarily a book about readers and writers.

Parts of this novel are almost like a blueprint to short story writing. There’s a lot of value in watching how Garp uses his real-world experiences to create his outlandish stories. I loved the relationship between him and Wolf- that sort of close author-editor bond is rare if not totally extinct nowadays and it’s cool to see what it brought to both Jenny and Garp’s work.

Speaking of Wolf, the dialogue between him and Jillsy on why Jillsy would continue to read a book that so greatly disturbed and offended her is truly wonderful. It’s one of those scenes you can look back on when you’re searching for motivation to go forward with your own work. Her definition of a “true” book as one that shows the most believeable thoughts and behaviors of real people deeply resonated with me. Throughout the entirety of it’s runtime this story also teaches one of the most important lessons any sort of artist needs to hear, which is: your art is inevitably going to be misunderstood and how you react to that will completely determine your future. On the basis of these and it’s many other thought-provoking comments on reading and writing, I highly recommend The World According to Garp.

One particular line now goes through my head when I hear of a new mass shooter in the news: “He was a man who pitied himself so blindly that he could make absolute enemies out of people who contributed only the ideas to his undoing.” What a perfectly harrowing sentence.

I would be remiss not to mention Roberta. I thought she was great trans representation- interesting and quirky backstory, provided crucial emotional support to both Jenny and Garp, and the one time Garp makes a nasty remark to her he immediately apologizes and affirms her. This is a very empathetic and humanizing portrayal of a trans woman- which might be a surprising thing to hear about a book published in 1978. The fact that she used to be a Philadelphia Eagle was so cool, I thought that really highlighted the unique life experiences we have as a result of our transness and made her truly stand out in the cast despite being only a minor character. This is a delightfully trans-friendly book!

Ending with a small anecdote, since I’m not a professional reviewer, just some guy on the internet: I’ve long been plagued with irrational fears of supernatural and extraterrestrial beings. I don’t believe they’re real but some deeper part of me that operates independently of all logic is thoroughly convinced otherwise. The being I’m most terrified of encountering is also the most harmless that I know of: Long Horse. Long Horse is a very skeletal-looking horse with a seemingly infinite neck; it only peeks around corners and will never show it’s full body. It doesn’t exist to hurt you, only to act as a very grim omen. If you see Long Horse, something terrible is certain to happen to you soon. Its presence is almost like a cosmic apology- the universe maybe feeling a little regretful of just how badly it’s about to fuck you over.

Reading about the Under Toad, I couldn’t get Long Horse out of my mind. These are eerily similar concepts but the Under Toad is almost like a real, physical force to Garp’s family in the way that it’s woven into the story. The existential horror of the Under Toad worked particularly well for me because it’s already a fear and a kind of symbolism I’m intimately familiar with. But even if I didn’t have this preexisting fear of impossibly large but harmless animals I think reading about the pure dread that the Under Toad imposed upon the whole main cast would’ve spooked me.

This book is about a lot of things. You could pick out any of the main themes and arguing the book is wholly about them wouldn’t be difficult. If you are a new parent dealing with the anxieties of living in a dangerous world, you’ll find companionship and understanding here. If you’re grieving the loss of a parent or child you’ll get the same- one of the most central themes is of death. If you’re interested in this purely as a piece of feminist lit, you can certainly read and analyze it that way and there’s much to be said about it from that perspective. But to me, as a reader and a writer (and a man who always reads authors notes and introductions, and so usually can somewhat guess the author’s intent), this is primarily a book about readers and writers.

Parts of this novel are almost like a blueprint to short story writing. There’s a lot of value in watching how Garp uses his real-world experiences to create his outlandish stories. I loved the relationship between him and Wolf- that sort of close author-editor bond is rare if not totally extinct nowadays and it’s cool to see what it brought to both Jenny and Garp’s work.

Speaking of Wolf, the dialogue between him and Jillsy on why Jillsy would continue to read a book that so greatly disturbed and offended her is truly wonderful. It’s one of those scenes you can look back on when you’re searching for motivation to go forward with your own work. Her definition of a “true” book as one that shows the most believeable thoughts and behaviors of real people deeply resonated with me. Throughout the entirety of it’s runtime this story also teaches one of the most important lessons any sort of artist needs to hear, which is: your art is inevitably going to be misunderstood and how you react to that will completely determine your future. On the basis of these and it’s many other thought-provoking comments on reading and writing, I highly recommend The World According to Garp.

One particular line now goes through my head when I hear of a new mass shooter in the news: “He was a man who pitied himself so blindly that he could make absolute enemies out of people who contributed only the ideas to his undoing.” What a perfectly harrowing sentence.

I would be remiss not to mention Roberta. I thought she was great trans representation- interesting and quirky backstory, provided crucial emotional support to both Jenny and Garp, and the one time Garp makes a nasty remark to her he immediately apologizes and affirms her. This is a very empathetic and humanizing portrayal of a trans woman- which might be a surprising thing to hear about a book published in 1978. The fact that she used to be a Philadelphia Eagle was so cool, I thought that really highlighted the unique life experiences we have as a result of our transness and made her truly stand out in the cast despite being only a minor character. This is a delightfully trans-friendly book!

Ending with a small anecdote, since I’m not a professional reviewer, just some guy on the internet: I’ve long been plagued with irrational fears of supernatural and extraterrestrial beings. I don’t believe they’re real but some deeper part of me that operates independently of all logic is thoroughly convinced otherwise. The being I’m most terrified of encountering is also the most harmless that I know of: Long Horse. Long Horse is a very skeletal-looking horse with a seemingly infinite neck; it only peeks around corners and will never show it’s full body. It doesn’t exist to hurt you, only to act as a very grim omen. If you see Long Horse, something terrible is certain to happen to you soon. Its presence is almost like a cosmic apology- the universe maybe feeling a little regretful of just how badly it’s about to fuck you over.

Reading about the Under Toad, I couldn’t get Long Horse out of my mind. These are eerily similar concepts but the Under Toad is almost like a real, physical force to Garp’s family in the way that it’s woven into the story. The existential horror of the Under Toad worked particularly well for me because it’s already a fear and a kind of symbolism I’m intimately familiar with. But even if I didn’t have this preexisting fear of impossibly large but harmless animals I think reading about the pure dread that the Under Toad imposed upon the whole main cast would’ve spooked me.

This book is really good.

It feels current. It feels every bit as contemporary as when the author wrote it and - as he put it himself forty years later - that feels incredibly disturbing. Because if this was all so clear to John Irving 40 years ago - and we still ended up here, now - well it makes you wonder about the whole endeavor of knowing things at all and whether such behavior yields results of any form. If John Irving wrote a book that explains division and intolerance - and it’s devastating effects on both sides of that division and on both ends of that intolerance - if he wrote that book forty years ago and here we are still divided and more intolerant than ever - and in much the same way - well then he wasn’t so much describing a moment in American history as he was describing America. And possibly humanity.

But the book is not just big ideas. It’s really a small story of a truly independent woman - Jenny - and an everyman - Garp.

Let’s start with Garp.

Garp begins the book a clueless child grasping at adulthood without any idea how to find it and matures into an independent, combative, impulsive adolescent man. Marriage and fatherhood don’t so much remove these impulses as transform them; as a new husband he takes up adultery. As a new father he ‘is so concerned to protect his children from harm that he ensures it.’ As a successful writer he picks fights needlessly and against all good advice and those fights get him killed. But as a mature husband he struggles to be more responsible and forgives his wife’s adultery. As a caring parent he moves on campus to ensure his son receives a good education. As a seasoned writer he eventually apologizes for his offensive editorial. He tries to embrace some of his mother’s spirit while remaining stand-offish toward feminism. He tames his ordinary flaws without aspiring toward or even acknowledge extreme virtue. He gradually, as a writer, loses creative possibility while he adds an ability to capture humanity. He trades his ambition for tradition, comfort, familiarity. In short, if Garp becomes better over the course of this book but it is not the result of a quest or a potion or some deep understanding he wants to bring back go the world - it is because he has bumped his head against the walls of lifes maze and moved forward instead of stopping. He embodies this gradual, inevitable, even worn down type of understanding that comes with time and can come about no other way. He is all of us men.

So what does that make his mother, Jenny.

Well Jenny does not change, really. She begins the book a caring, thoughtful, insightful, strong and independent woman and she ends the book that way. We are introduced to her stabbing an aggressive young male who attempted to sexually assault her. And we see her die when she is shot by an aggressive middle aged male who is upset with her for inspiring his wife to leave home, so he would stop physically assaulting her. And along the way? She seems to live her whole life for the benefit of her child and women who need help. She works as a nurse in her youth, curing first soldiers and then the children of her son’s boarding school and then - after she has derived great wealth from writing her autobiography - she houses women in her large home by the sea, providing respite to their souls. She has won no new knowledge, completed no quest, learned nothing mysterious that she must bring back to humanity. Instead she lives by a simple code and she lives by it consistently from the first time we meet her to her violent death. She reflects these core human values: caring, nurturing, selflessness, and also protectiveness. If she changes at all, it is only to allow these values to extend from her son to all women.

Is if over-simplistic to call Garp an ideal type of a particular maleness - its characteristic arc from brash independence to calmed belonging and Jenny one of a particular femaleness - its consistent, unflappable humanity. Probably.

So why don’t we care more when they die? Was I the only one who experienced this? Walt’s death devastated me. I could barely keep reading. But Jenny’s death felt inevitable. Coldly foreshadowed and somehow necessary. Garp’s almost like an afterthought - a quick playing out of the inevitable consequences of that aggression that we see him put on display in various forms thru the book. And that’s sort of where the little story and the big story meet, I think. The little story: Walt’s death is tragic because we know the individual motives of every actor: these are decent people caught up in a terrible Rube Goldberg that we have to watch play out to its inevitable, jarring conclusion. But Garp and Jenny are players on a violent stage - the big world of division and aggression. As players on that stage, violence seems not jarring or shocking but a matter of course. Jenny steps onto this stage thru her writing and then participation in a community and Garp thru his writing and then attacks on a community. These are people to whom violence can happen. It is only remarkable what crime gets each killed. Garp dies because of his aggression - his badness or at least actions he regrets - even tries to undo, Jenny dies because she cared for someone who could not care for herself. She dies for her goodness. And that honestly feels like the most predictable part of the story.

I loved this book,

FIVE STARS

It feels current. It feels every bit as contemporary as when the author wrote it and - as he put it himself forty years later - that feels incredibly disturbing. Because if this was all so clear to John Irving 40 years ago - and we still ended up here, now - well it makes you wonder about the whole endeavor of knowing things at all and whether such behavior yields results of any form. If John Irving wrote a book that explains division and intolerance - and it’s devastating effects on both sides of that division and on both ends of that intolerance - if he wrote that book forty years ago and here we are still divided and more intolerant than ever - and in much the same way - well then he wasn’t so much describing a moment in American history as he was describing America. And possibly humanity.

But the book is not just big ideas. It’s really a small story of a truly independent woman - Jenny - and an everyman - Garp.

Let’s start with Garp.

Garp begins the book a clueless child grasping at adulthood without any idea how to find it and matures into an independent, combative, impulsive adolescent man. Marriage and fatherhood don’t so much remove these impulses as transform them; as a new husband he takes up adultery. As a new father he ‘is so concerned to protect his children from harm that he ensures it.’ As a successful writer he picks fights needlessly and against all good advice and those fights get him killed. But as a mature husband he struggles to be more responsible and forgives his wife’s adultery. As a caring parent he moves on campus to ensure his son receives a good education. As a seasoned writer he eventually apologizes for his offensive editorial. He tries to embrace some of his mother’s spirit while remaining stand-offish toward feminism. He tames his ordinary flaws without aspiring toward or even acknowledge extreme virtue. He gradually, as a writer, loses creative possibility while he adds an ability to capture humanity. He trades his ambition for tradition, comfort, familiarity. In short, if Garp becomes better over the course of this book but it is not the result of a quest or a potion or some deep understanding he wants to bring back go the world - it is because he has bumped his head against the walls of lifes maze and moved forward instead of stopping. He embodies this gradual, inevitable, even worn down type of understanding that comes with time and can come about no other way. He is all of us men.

So what does that make his mother, Jenny.

Well Jenny does not change, really. She begins the book a caring, thoughtful, insightful, strong and independent woman and she ends the book that way. We are introduced to her stabbing an aggressive young male who attempted to sexually assault her. And we see her die when she is shot by an aggressive middle aged male who is upset with her for inspiring his wife to leave home, so he would stop physically assaulting her. And along the way? She seems to live her whole life for the benefit of her child and women who need help. She works as a nurse in her youth, curing first soldiers and then the children of her son’s boarding school and then - after she has derived great wealth from writing her autobiography - she houses women in her large home by the sea, providing respite to their souls. She has won no new knowledge, completed no quest, learned nothing mysterious that she must bring back to humanity. Instead she lives by a simple code and she lives by it consistently from the first time we meet her to her violent death. She reflects these core human values: caring, nurturing, selflessness, and also protectiveness. If she changes at all, it is only to allow these values to extend from her son to all women.

Is if over-simplistic to call Garp an ideal type of a particular maleness - its characteristic arc from brash independence to calmed belonging and Jenny one of a particular femaleness - its consistent, unflappable humanity. Probably.

So why don’t we care more when they die? Was I the only one who experienced this? Walt’s death devastated me. I could barely keep reading. But Jenny’s death felt inevitable. Coldly foreshadowed and somehow necessary. Garp’s almost like an afterthought - a quick playing out of the inevitable consequences of that aggression that we see him put on display in various forms thru the book. And that’s sort of where the little story and the big story meet, I think. The little story: Walt’s death is tragic because we know the individual motives of every actor: these are decent people caught up in a terrible Rube Goldberg that we have to watch play out to its inevitable, jarring conclusion. But Garp and Jenny are players on a violent stage - the big world of division and aggression. As players on that stage, violence seems not jarring or shocking but a matter of course. Jenny steps onto this stage thru her writing and then participation in a community and Garp thru his writing and then attacks on a community. These are people to whom violence can happen. It is only remarkable what crime gets each killed. Garp dies because of his aggression - his badness or at least actions he regrets - even tries to undo, Jenny dies because she cared for someone who could not care for herself. She dies for her goodness. And that honestly feels like the most predictable part of the story.

I loved this book,

FIVE STARS

Great book. Ups and downs. Slow and fast. All good.

I first read this as a teenager and didn't fully appreciate it. At the time, it just seemed really weird and overly sexual. Which it is. But wow, there's so much happening in this novel, both on the surface and in a literary way. And dear lord, the under toad. I hear you, Irving. And I see the toad everywhere.

See why thousands of readers are using Bookclubs to stay connected.